This is Part 1 of our 6-part Deep Dive series on neuromorphic computing—the brain-inspired processors achieving 1,000× efficiency improvements over GPUs at the edge.

[🧠] Sapien Fusion Deep Dive Series | February 4, 2026 | Reading time: 5 minutes

Why GPU Architecture Can’t Scale to the Edge

To understand why neuromorphic computing matters now, you need to understand what GPUs were never designed to do.

NVIDIA’s dominance in AI acceleration stems from a simple insight: training and running neural networks requires massive parallel computation—exactly what GPUs, originally designed for rendering graphics, excel at executing. For centralized data centers processing enormous models where electricity costs pale compared to capital expenditure on hardware, GPUs remain unbeatable.

The edge is different.

Autonomous robots patrolling oil refineries can’t tether to wall power. Drones monitoring agricultural fields need to cover hundreds of acres on a battery. Prosthetic limbs with AI-driven motor control can’t heat tissue with hundreds of watts of processing. Autonomous vehicles require sub-millisecond perception latency for collision avoidance—frame-based GPU processing struggles to deliver consistent sub-50ms response times.

Traditional processor architecture hits three fundamental walls at the edge.

The Power Wall

GPUs consume 10-60 watts for mobile variants, 300+ watts for high-performance modules. Battery capacity scales linearly with weight and cost. Processing efficiency determines operational duration. The physics are unforgiving.

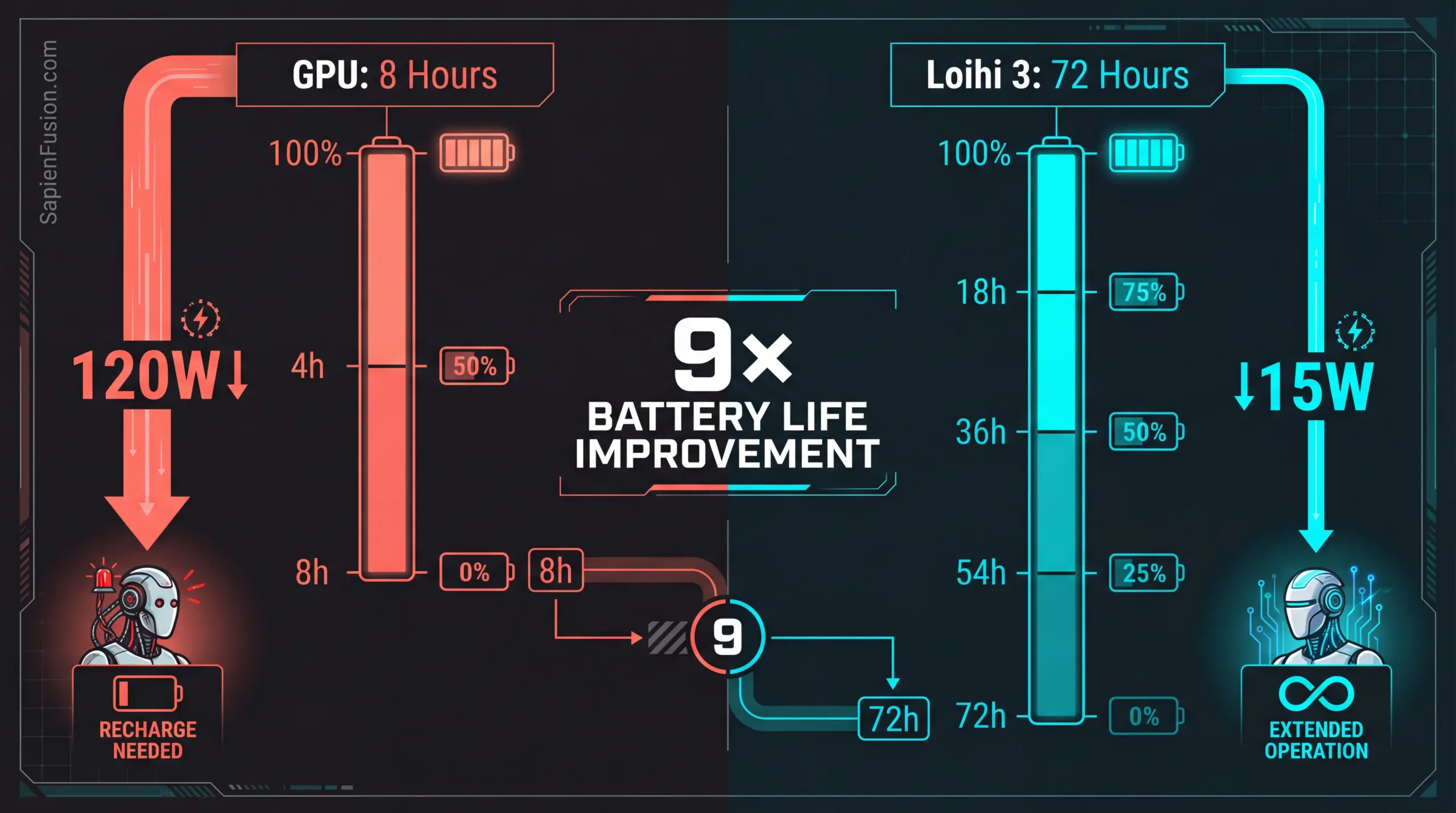

A warehouse inspection robot equipped with NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX operating 8 hours requires approximately 120 watt-hours of battery capacity at 15W typical power draw. Adding the battery weight—roughly 400-600 grams for lithium-ion at current energy densities—plus thermal management systems compounds the problem.

Now extend that operational requirement to 72 hours, the duration Intel’s Loihi 3 achieves on the ANYmal quadruped. The GPU approach would require 1,080 watt-hours of battery capacity, translating to 3.6-5.4 kilograms of additional battery weight. That’s before accounting for the structural reinforcement needed to carry the extra mass.

The economic reality cascades through every deployment decision. Industrial robotics deployments calculate the total cost of ownership over 5-10 year lifespans. Every kilogram of battery weight requires stronger motors that consume more power and cost more to manufacture. The chassis needs reinforcement, raising manufacturing costs. Payload capacity decreases, reducing operational utility. Charging infrastructure expands, increasing capital expenditure.

Mobile robotics vendors face a brutal equation: GPU processing power versus operational viability. Most choose reduced AI capability to achieve practical battery life. Neuromorphic processors eliminate this tradeoff entirely.

The Latency Wall

Conventional processors operate in fixed temporal frames regardless of whether input data changes. A security camera processing empty hallways consumes the same power as processing active intrusions. This frame-based paradigm wastes enormous energy processing redundant information while introducing latency through buffering and batch processing.

Standard computer vision pipelines operate at 30-60 frames per second. Each frame requires sensor capture, taking 16-33 milliseconds, data transfer to the processor consuming 2-5 milliseconds via standard interfaces, processing through a neural network requiring 10-30 milliseconds on a GPU, and decision output demanding another 1-5 milliseconds. Total latency ranges from 29-73 milliseconds under ideal conditions, before accounting for variable processing loads or thermal throttling.

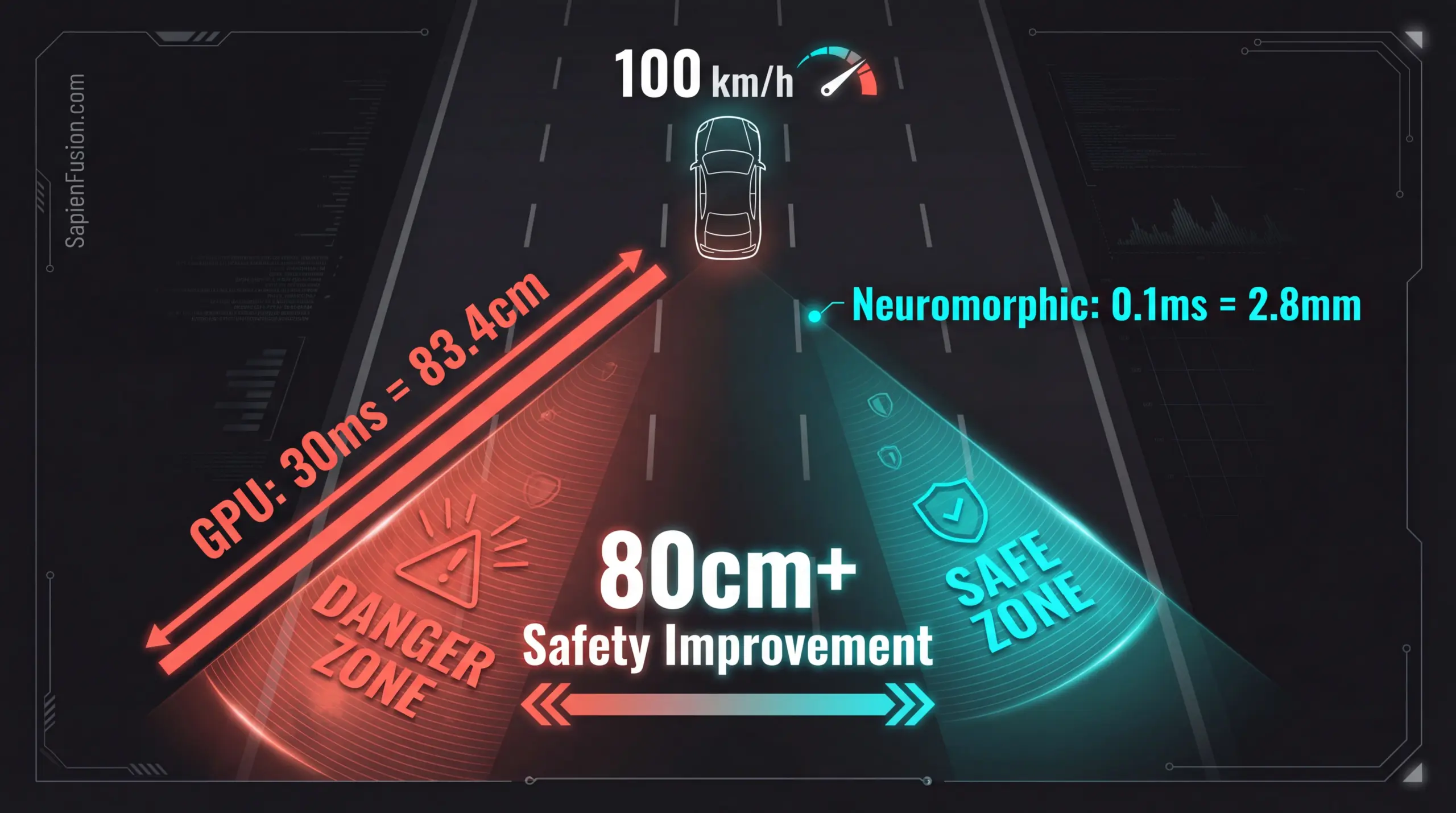

When milliseconds matter, these delays prove catastrophic. Mercedes-Benz research targeting 0.1-millisecond pedestrian detection isn’t pursuing marginal improvements—every millisecond of latency translates directly to stopping distance at highway speeds.

Consider a vehicle traveling 100 kilometers per hour, covering 27.8 meters per second. With 30ms GPU latency, the vehicle travels 83.4 centimeters before detection occurs. With 0.1ms neuromorphic latency, the travel distance before detection drops to 2.8 millimeters. That 80+ centimeter difference represents the margin between collision avoidance and catastrophic failure. Frame-based processing fundamentally cannot achieve sub-millisecond response because the architectural model requires buffering and batch operations.

Event-driven neuromorphic approaches respond to changes as they occur, not at fixed intervals. A neuromorphic vision system processing a pedestrian stepping into the roadway triggers an immediate spike response in 0.1 milliseconds. Static background requires no processing and consumes zero power. Moving vehicles receive continuous tracking with computation proportional to motion. This event-driven approach eliminates both unnecessary processing and buffering latency simultaneously.

The Memory Wall

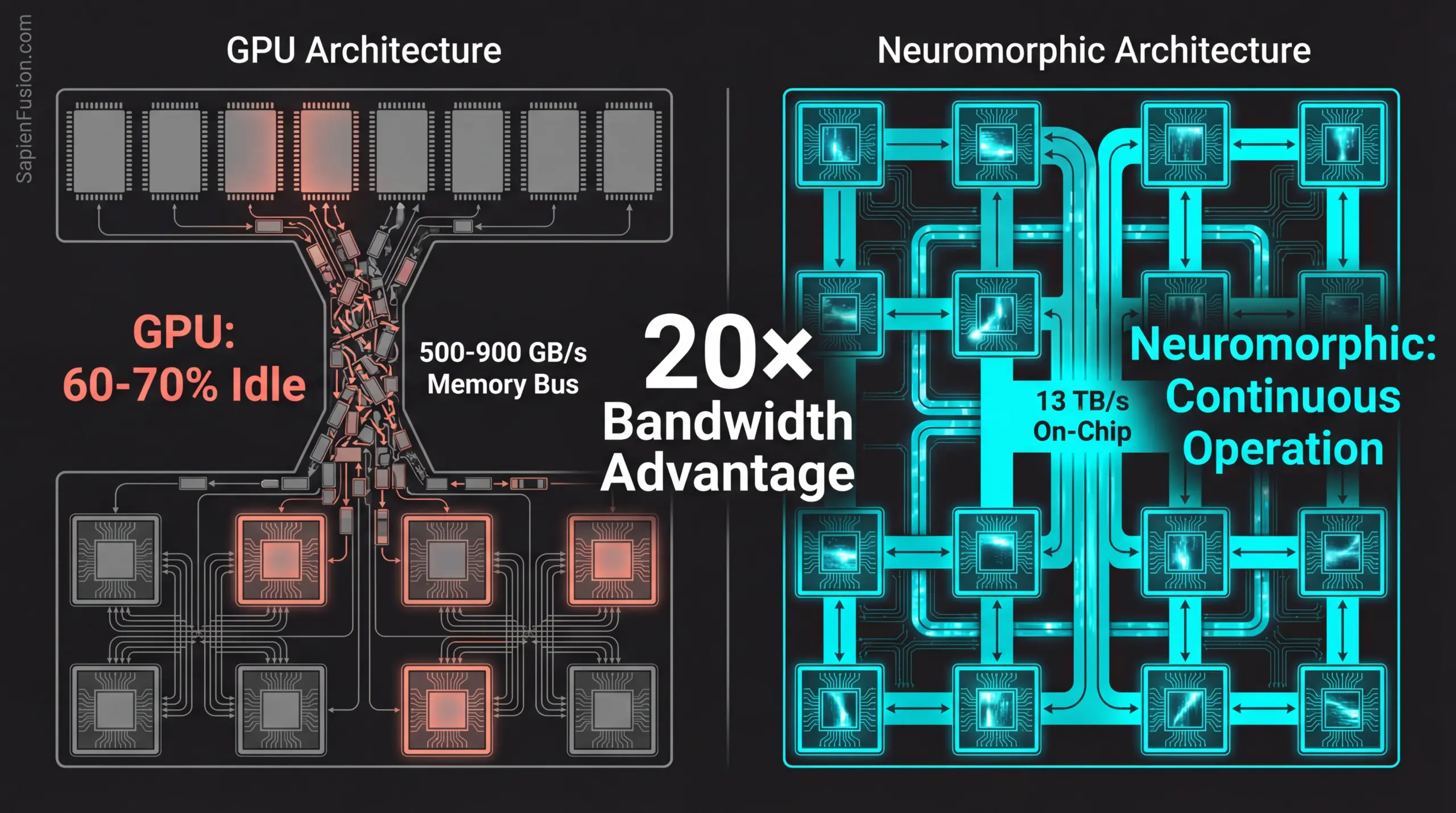

The von Neumann bottleneck—the physical separation between processing units and memory—forces constant data shuttling across bandwidth-limited interconnects. As processor efficiency compounds exponentially following Moore’s Law, memory bandwidth improvements lag dramatically behind, doubling every 3-4 years compared to processor performance doubling every 18-24 months. This growing gap creates catastrophic inefficiency for AI inference.

Neural network inference requires billions of simple arithmetic operations accessing vast model weights. A typical ResNet-50 computer vision model contains 25.6 million parameters. Processing a single 224×224 image requires 4 billion multiply-accumulate operations while accessing all 25.6 million parameters—102.4 megabytes at 32-bit precision—in multiple passes through the data.

On conventional GPU architecture, weights reside in high-bandwidth memory while processing cores request data across the memory bus, constrained to 500-900 gigabytes per second for high-end GPUs. Processing cores idle 60-70% of their time waiting for data rather than computing. When processing elements spend the majority of their time waiting for memory rather than executing computations, effective performance drops to 30-40% of the theoretical maximum. Energy consumption remains constant whether cores compute or idle-wait, creating massive power consumption for mediocre throughput.

IBM NorthPole’s solution co-locates 224 megabytes of memory directly on-chip with 256 processing cores, achieving 13 terabytes per second internal bandwidth—roughly 20× higher than high-end GPU memory buses. Entire models reside on-chip. No external memory access required. Processing cores never idle waiting for data. The efficiency improvement reaches 72.7× for language model inference versus GPU equivalents.

Intel Loihi 3 distributes synaptic weights directly adjacent to neurons, placing memory immediately beside processing. Event-driven activation eliminates unnecessary memory access when neurons don’t fire; their associated memory remains untouched, consuming zero power. Combined with temporal sparsity, where most neurons remain inactive most of the time, the architecture achieves 1,000× efficiency advantages for event-driven workloads.

Why These Walls Matter Now

For two decades, GPU vendors addressed power, latency, and memory constraints through incremental optimization. More efficient manufacturing processes progressed from 7nm to 5nm to 3nm nodes. Better cooling solutions employed liquid cooling and vapor chambers. Smarter power management implemented dynamic voltage and frequency scaling. Faster memory technologies advanced from GDDR6 to HBM2 to HBM3. These optimizations delivered 2-3× improvements per generation—valuable, but insufficient for edge deployment requirements.

Industrial robotics requires 10-50× battery life improvements to be economically viable. Autonomous vehicles require 10-100× latency reductions for safety margins. Mobile AI devices require 5-20× power reductions for all-day operation. Incremental GPU optimization cannot bridge these gaps. The architectural paradigm itself imposes fundamental limits.

Neuromorphic processors attack all three walls simultaneously. Event-driven processing combined with temporal sparsity delivers 5-1,000× power reduction. Asynchronous event response enables sub-millisecond capability. Memory co-location or distribution eliminates the bottleneck. This isn’t optimization—it’s architectural reimagination enabling entirely new deployment categories.

The Strategic Implications

Organizations deploying AI at the physical edge face a decision point. Continuing GPU-centric approaches means accepting operational constraints, including limited battery life and latency limitations, deploying reduced-capability models that fit within power budgets, requiring extensive charging infrastructure for mobile systems, and remaining limited to applications where these tradeoffs prove acceptable.

Adopting neuromorphic architectures enables operational durations previously impossible, like 72-hour robot operation. It permits safety-critical applications requiring sub-millisecond response. It allows deploying sophisticated AI at locations without power infrastructure. It captures competitive advantages in emerging application domains.

The competitive window narrows rapidly. Automotive manufacturers integrating neuromorphic perception establish measurable safety advantages and economic benefits. Industrial robotics vendors achieving ninefold battery life improvements capture deployment opportunities that competitors cannot serve. Edge AI providers delivering sub-millisecond latency enable application categories that GPU architectures fundamentally cannot address.

First movers establish market positioning before neuromorphic integration becomes table stakes. Neuromorphic deployment requires 18-36 months from evaluation to production. Market inflection arrives in 2027-2028 for automotive and industrial robotics. Software maturity needs 2-3 years for mainstream developer tooling. Organizations beginning evaluation now achieve production deployment by late 2027. Those waiting face a disadvantage as early movers establish positioning.